Decolonizing AI: Reclaiming Technological Futures from the Global South

>A_SUMMARY_OF_MEETING_02

As AI technologies becomes increasingly central to shaping global futures, we at MOMSA are asking urgent and necessary questions: Who builds these technologies? Whose values do they encode? And who bears the costs?

In this short piece, I will highlight some interesting points of discussion that occurred in Mind Over Model South Africa’s (MOMSA) Third annual roundtable discussion that occurred on the 10th of April 2025.

The discussion centered around Gebru and Torres’s paper "The TESCREAL Bundle”1 alongside two journalistic pieces exposing the system’s underside. One revealed how OpenAI outsourced the psychic burden of cleaning toxic training data to underpaid Kenyan workers. Another examined Nvidia’s AI “factory” in Africa, framed as opportunity but functioning as digital extractivism. The mask of development hiding a logic of control.

No one in the conversation rejected technology. That would be naïve to think so. The real concern was with how the technology is used and who benefits from its deployment. Big Tech does not seek mutuality. It seeks obedience. Its ethos is to move fast, break social fabrics, and patch them with code. AI, in its current trajectory, does not dismantle power. It enforces it.

The conversation moved beyond ethics of AI2. It became a confrontation with the power of Big Tech itself. Technology is not separate from domination. In Africa, this is especially palpable. The continent holds the mineral infrastructure of the future. This makes it not only valuable, but dangerous. The continent’s wealth renders it vulnerable to external control, enforced through digital means. Sanctions, foreign dependency, and embedded hierarchies deepen this asymmetry.

There was also deep reflection on the internal complexity of Africa. The continent is marked by radical diversity. Multiple languages, cultures, and value systems coexist, sometimes in tension. Yet this plurality should not be seen as a barrier to global AI ethical frameworks. It is a challenge to the very idea of universality as imagined by the West. African diversity is not noise. It is signal. It demands a redefinition of what counts as intelligence, as value, as humanity.

Skepticism toward artificial general intelligence (AGI) permeated the discussion. Current systems are incapable of self-awareness or critical reasoning. They do not understand; they compute. The illusion of sentience masks their rigid frameworks. These models are environmentally destructive and epistemically brittle. They cannot adapt to African contexts because they were never built to understand them. They are trained on narrow data, from narrow minds, for narrow ends.

A deeper issue emerged around the ideology of scientism. The belief that science holds universal truth flattens human experience. It delegitimizes other ways of knowing. AGI, as it is currently pursued, is founded on this fallacy. It encodes the perspectives of particular cultures, histories, and power structures while pretending to speak for all. This creates systems that replicate bias with machine precision. Confidence in these machines becomes dangerous when it overrides lived realities. When a model decides outcomes and people can no longer speak for themselves, we enter a new form of colonial control, this time enforced by algorithms.

Surveillance technologies were cited as examples of this shift. Smart cameras justified through traffic management or security are also tools of monitoring and compliance. Africa has adopted much of this technology without reconfiguring its intent. Western systems are imported wholesale because they come cloaked in the aura of science and modernity. But this is not neutral progress. It is infrastructural dominance. It installs a global operating system to which everyone is expected to submit.

The real threat posed by Big Tech is not just technological dependency. It is political capture through code. The question is not whether AI can serve Africa. The question is whether Africa can assert sovereignty over AI. Not to be a testbed, not to be a backend, but to be an origin point for new futures.

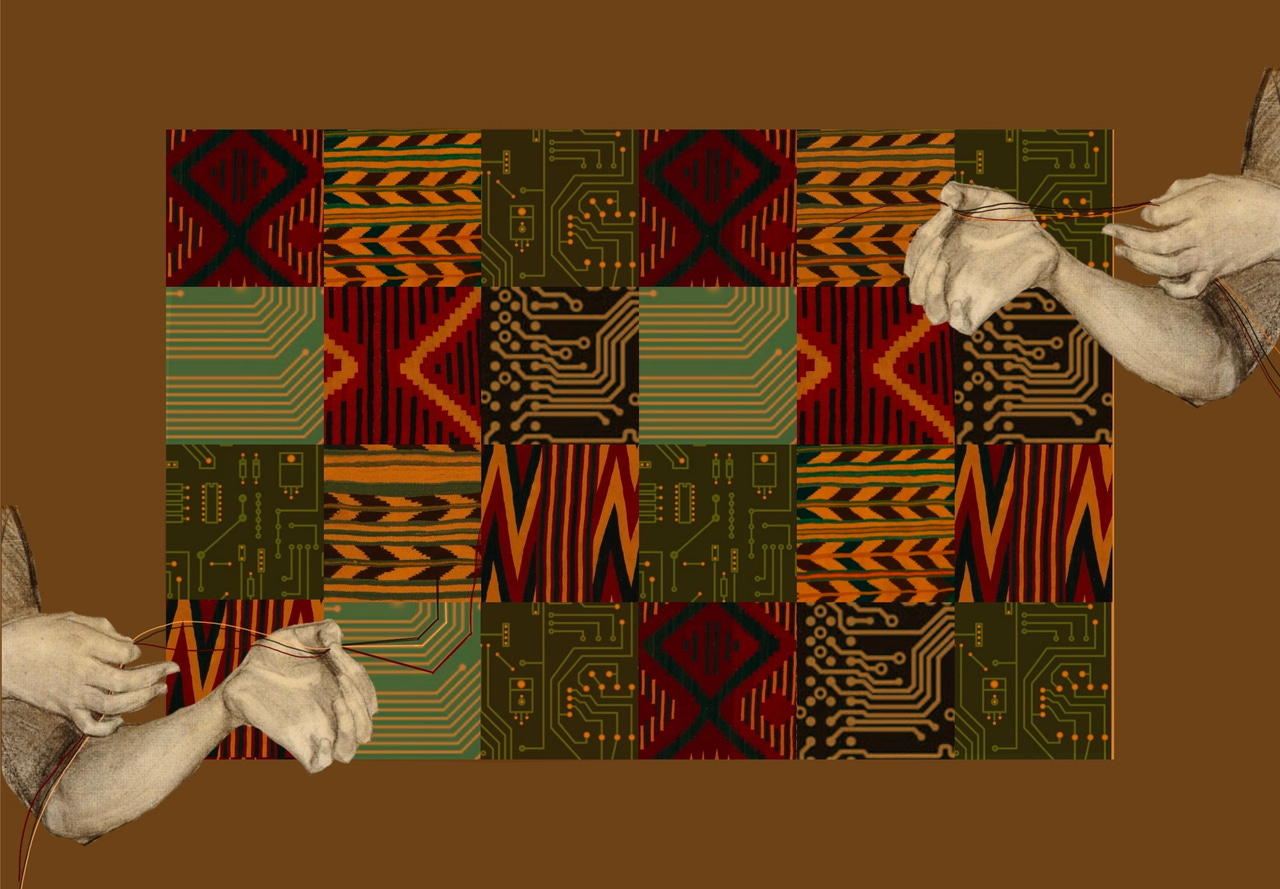

The response cannot be mild reform. It must be foundational. African thinkers, builders, and communities must not simply be included in someone else’s vision. They must define the vision itself. This means dismantling the assumptions baked into current AI systems. It means refusing universals that deny plurality. It means designing intelligence that emerges from the ground, from struggle, from lived contradiction.

We are not dealing with tools. We are dealing with metaphysical weapons. The machines are learning, but they are not listening. If we do not interrupt this process, we will find ourselves governed by systems that only understand power, not people.

Ultimately, the discussion made it clear that decolonizing AI goes beyond just ethical audits or diversity checklists. It demands a fundamental shift in how we think about technology, power, and the future. Africa’s diverse values and lived experiences can and should inform global AI ethics, so that we create a world where technology works for everyone, not just the powerful few.

This piece was written by Sven Ronen, founder of MOMSA and Masters candidate at the University of Pretoria.